The first part of the Battlestar Galactica finale (Daybreak, Part I) has now aired, and next Friday will have the two-hour conclusion of the story.

Category: Culture

Will Paint for Food (or possibly beer)

(from my blog Old World Swine)

Well,

life is full of surprises, ain't it? Remember a while ago, when I was

asking readers to send in their impressions of the local and personal

effects of the recession and the stock market crash? I made my own

observation at the time that I was seeing very little evidence of it,

as yet, aside from lower gas prices. Then I did make note that some

local stores would be closing (a Starbucks, Circuit City, Linens &

Things).

Now the evidence I asked about has come up and kicked me in the aft end… as of Friday I was given the official two week notice that my job is being cut. My last check will arrive in a month.

It

was a surprise, but not a deep shock. I had been aware for some time

that the amount of work they had for me to do was steadily declining.

When I started in my position, I was kept busier than a grasshopper

kicking the seeds out of a watermelon, but in recent months I had not

only begun to somewhat, shall we say, stretch the projects I

had, but had actually started to create my own projects (which has

never been in my job description). I began to create a library of stock

illustrations that (based on my experience) I thought might be useful

in the future. As this library expanded and went largely unused,

though, it began to feel very futile. I was sitting at my desk, drawing

a check and drawing (literally) whatever I thought made sense… food,

mostly. Our company had used a lot of food art in their packaging.

I had the odd hot-potato-we-must-have-this-by-Tuesday

job to break the monotony, but it began to feel like my own company was

sort of holding me on a retainer for those increasingly rare instances

when I was actually needed. I began to get frustrated and a bit

depressed, which is a horrible position for a Christian.

The

Christian should always be eager to go wherever God leads and do

whatever is needed without complaint and with sincere gratitude.

Constant thankfulness should be the default position for any

follower of Jesus. Life is just too variously and mind-bogglingly

wonderful – too "lopsidedly benevolent", as I have put it before – to

allow oneself to mope because this or that aspect of it isn't meeting

one's expectations.

So, when I began to get frustrated and

depressed at my job, I knew something was deeply wrong. I was also

feeling a more insistent desire to move ahead with my fine art, and the

day job (with its two-hour daily commute) seemed to suck the life and

energy (and creativity) out of me. But I have a family to support, and

as long as I could keep the job, I figured that was where God wanted me

to be.

So, it looks like I'll have a lot more time to devote to

the fine art and to Catholic (and other) illustration. I'll be putting

up some illustration and cartoons from time to time, as well as my

painting. There are new avenues open to me, now, in terms of getting my

art out there in front of people. As it turns out, instead of painting

this past weekend, I spent the time getting my Etsy store up and

running. Etsy is a cool, fairly new outlet for handmade goods and art,

and I've been meaning to get my online store – er, gallery – started for some time. I may even have time to begin that series of the Mysteries of the Rosary I have been wanting to do.

So, check it out. Tell your friends!

(Thats www.oldworldswine.etsy.com)

The Esty site will most likely be where I direct people from my Daily Painting blog

from now on, though I have had some early success with E-bay and may

continue to use it. I don't know. You would think I might have more

time to blog here at OWS, now, but that's not likely. I'm going to have

to hit the ground running if I want to maintain any kind of steady

income in all this, and so I'll be treating the fine art as a full-time

job (and possibly more). I'm grateful, though, that I'll be able to

make it to daily Mass.

Your prayers would be most

appreciated. At the moment I'm kind of excited at the possibilities,

and am looking at it as an adventure… Wheee! another big dip on the

roller coaster of life… but it is easy to talk that way when the

checks are still coming. We have been through some lean times before,

and the romance of such a position fades quickly. The sense of

adventure turns into a rather permanent knot in the stomach.

As Chesterton has said (and I have often quoted before);

Our society is so abnormal that the normal man never dreams of

having the normal occupation of looking after his own property. When he

chooses a trade, he chooses one of the ten thousand trades that involve

looking after other people's property.

I have to say that, as a Distributist, I do look forward to looking after my own property.

And the Final Cylon Is . . .

The final ten episodes of Battlestar Galactica start airing this Friday, and the producers plan to answer a bunch of questions, some of which have been around since the beginning of the show and some of which were only recently introduced: What happened to Earth? What are the Virtual "Head" beings (e.g., Head Six, Head Baltar) that only some people see? Can Human and Cylon live together? Who lives and who dies? And, of course, who is the final Cylon?

The final ten episodes of Battlestar Galactica start airing this Friday, and the producers plan to answer a bunch of questions, some of which have been around since the beginning of the show and some of which were only recently introduced: What happened to Earth? What are the Virtual "Head" beings (e.g., Head Six, Head Baltar) that only some people see? Can Human and Cylon live together? Who lives and who dies? And, of course, who is the final Cylon?

I'm going to tell you.

Or at least I'm going to tell you who I think it is.

I've made a significant number of BSG predictions before and gotten more than my share right, so I'm going to put my cards on the table here and tell you who I think the clues point to.

If I can shift from a cards metaphor to a dice metaphor, sometimes you have to roll the hard six, so here goes.

Continued below the fold for those who don't want to read this speculation.

Check Out Tim Jones’ New Daily Painting Blog!

Hey, Tim Jones, here.

Today marks the *official* launch of my long anticipated (by me, anyway… I always was a procrastinator) Daily Painting blog.

Now, "daily painting" doesn't mean necessarily a painting a day…

it just means I plan to paint daily, and I'll offer that work on

the new blog (via e-bay). In practice I look for this to shake out at about

3 paintings a week, though that may increase as things progress.

These are mainly small – even miniature – pieces, but made with all the care I would give to any of my larger artworks.

I will also soon be offering some very special pricing on some of the art from my old fine art website, as I move into this new strategy.

Up

until very recently, making a living in original fine art was mainly a matter

of finding gallery representation (in viable commercial galleries) and

building a reputation (and generating income) that way. Finding

publicity through art competitions and art publications could help to

make you more attractive to these galleries. But the whole process of

vetting and courting galleries – in addition to actually trying to get

any work done (on top of having, like, a day job) – has been like hiking through molasses. One needs almost

to work full time just on marketing, scheduling competitions,

hob-nobbing and the like. It doesn't help that I'm such an intense

introvert.

With the advent of the internet, though, there are now

more and more artists taking their work directly to the public. It's a

transition I've been turning over in my mind for some time, but

hesitated to jump into.

I have now made the jump. That means that

the prices I had on a lot of my artwork will be reduced because I no

longer need to consider the requirements of a third party (the

galleries) or worry so much about impressing collectors that might drop

by. So, in addition to the small daily painting pieces, watch for some

larger work as well.

The long and short is that I would rather

paint – and make my living from painting – than not. If that means

pricing my work so that it will be more accessible to a wider audience,

then that is a change I am happy to make. It could even be seen as very

Chestertonian… a Distributist approach to fine art.

I'll be

offering occasional opinions and commentary on my work interspersed

with with the new paintings, but the next several posts at the new blog will just be

new paintings offered for your viewing pleasure, with a link to the

e-bay auction page for each piece.

Do check in often. I hope you like what you see.

Oh! Also please feel free to drop a line in the combox.

Two more from YouTube — Christmas & Star Wars

EDIT: Comments below revised.

SDG here with another Christmas song from Straight No Chaser, this time a straight rendition of Silent Night.

And also, I can’t resist posting a non-Christmas acapella song pointed out to me by JA.o reader Matheus on another subject beloved of JA.o fans. I have a few comments on this one below — but don’t read the comments below until you’ve watched the second video!

Straight No Chaser – Silent Night

Star Wars – John Williams Tribute

Comments on the John Williams tribute below.

(you did watch it, right?)

-

HT to Bill for pointing this out: This song was written and recorded by an acapella group called Moosebutter. A different YouTube video is available showing , but not this recording of it (you can tell it’s the same voices, but not the same recording). The video above shows a “paid YouTuber” name Corey Vidal lip-synching a different recording of the song. Thos video was apparently made with Moosebutter’s cooperation, but lots of people (including me at first) haven’t glommed that Corey isn’t actually singing. Anyway, I’m keeping the Corey version here because the recording is cleaner, with less mugging, and I like the way it sounds better, but it does dampen my enthusiasm to know that that’s not the real guy singing.

-

One of my favorite bits is the E.T. theme, where they’re doing Luke complaining to Uncle Owen about not getting to go to Toshi Station for power converters — they get Luke’s whiny tone exactly right.

-

I also love the goofy dissonance between the soaring, majestic Jurassic Park theme and the sinister dialogue they put over it.

Decent Films doings: A good year for family films, part 2

SDG here with a follow-up to my June post on family films of 2008.

As the year draws to a close, it looks like my sense of 2008 as a good year for family films was on the money. In fact, the premise of my June post became a full-fledged article which appeared first in the December issue of Catholic World Report and is now available in an abridged version at Decent Films:

Family Films Move Forward in 2008

Unfortunately, many of the films that, in June, I was looking forward to hopefully didn't pan out. I knew some of them wouldn't pan out, but I was hoping for more than we got.

The one spectacular exception, of course, was Wall-E, the crown jewel of the year's family films, as I hoped it would be.

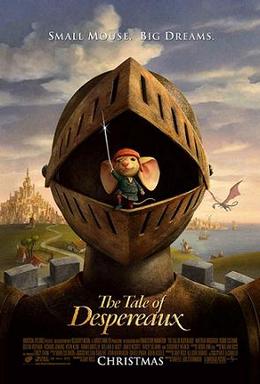

And today, a worthwhile film opens that wasn't even on my radar in June: The Tale of Despereaux.

At least one other film, Bolt turned out to be better than I expected. OTOH, City of Ember turned out to be a visually stylish disappointment, kind of cool but not very good. Journey to the Center of the Earth was a little more fun, but also not exactly good.

Fly Me to the Moon was barely a flyweight contribution (and the buzz I heard on Armstrong's involvement was wrong — it was Buzz Aldrin who voiced himself, which makes a lot more sense on multiple levels). And The Half-Blood Prince didn't even arrive — it was postponed until next year.

Still, between Wall-E, Horton Hears a Who, Kung Fu Panda, The Spiderwick Chronicles, Prince Caspian and The Tale of Despereaux, plus a raft of tol'able also-rans… not to mention, for families with older kids, The Express and Son of Rambow… definitely a good year, all in all.

Name-checked by Ebert — again!

SDG here with a non-election related post on some non-election coolness. (Pre-election coolness, actually, but I wanted to wait till now to blog about it.)

Incidentally, if you read the NCRegister.com blog, which I’ve cited in a number of recent posts, you may already be aware of this.

First, though, I just have to geek out a bit. Like many film critics writing today, I grew up watching Roger Ebert discuss movies with Gene Siskel on “At the Movies.” I remember watching them discuss certain movies in the early 1980s (e.g., Raiders, Superman II, Return of the Jedi).

I have the idea that the paper I delivered as a paperboy carried Ebert’s written reviews, and that I was reading them sometime in the early to mid-1980s. I may have I bought book editions of his reviews in college in the late 1980s; certainly by the time I had Internet access in the mid-1990s I was reading him every week, along with a few other favorites.

As an inveterate reader of all sorts of writing and an aspiring writer myself, I quickly came to appreciate Ebert’s literary skill and engaging voice as well as his critical insights. In many cases I enjoyed his reviews more than the movies he wrote about. In 2000, when I began writing faith-informed reviews and posting them on the earliest incarnation of Decent Films, Ebert was one of the touchstones I looked to in finding a voice of my own.

He was, and is, simply The Man.

One early piece I wrote that first year of writing film criticism was an essay on Scorsese’s The Last Temptation of Christ. It seemed to me an obvious test case of the style of writing I wanted to do — that is, to do film writing that was equally intelligible to my target religious audience and also to non-religious readers. (My model here was a writer even more profoundly influential on me than Ebert, C. S. Lewis.)

Few movies seemed as deeply polarizing to the two groups of readers than Last Temptation, so if I could make myself intelligible to these two groups of readers on this film, I could probably do it on any film.

I’m sure I read Ebert’s original review of Last Temptation, in which he argues that the film is not blasphemous, in preparation for writing my own. I didn’t quote it, although I did cite another review he wrote in 2000, for Spike Lee’s Bamboozled.

I never expected my Last Temptation essay to get much attention. I naively thought the controversy over that film was a closed chapter, and my essay was fundamentally written to satisfy myself that it could be done, and for the sake of a few readers who might care to look at it.

Much to my surprise, it has over the years consistently been among the most widely read essays at Decent Films. Feedback from readers has been fairly regular and all over the map (as I discussed a bit in a recent Decent Films reader mail column).

More recently, I’ve learned that my essay has been cited in more than one essay in a recent book on Last Temptation, Scandalizing Jesus. (One of the essays citing me was written by my friend and fellow critic Peter Chattaway; another, “Imaging the Divine,” is by Lloyd Baugh, whom I’ve never met.)

Anyway, last week I learned that my Last Temptation essay had been cited by Ebert himself in a new essay on Last Temptation that appeared both in his online “Great Films” series and also in Ebert’s new book Scorsese by Ebert.

As it happens, this isn’t the first time I’ve been name-checked by Ebert. He first quoted me in his review of Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ, regarding Gibson’s portrayal of the Jewish leaders. Just think, if controversial Jesus movies were a Hollywood staple, I might have gotten a guest spot on Ebert’s show.

What’s more, this time around Ebert credits my essay with persuading him that, in spite of his arguments to the contrary nearly two decades ago, Last Temptation is in fact “technically blasphemous.” He adds that he no longer thinks this matters, but still it’s a startling confirmation that I succeeded at least partly in what I set out to do in that essay. Here’s what he wrote:

The film is indeed technically blasphemous. I have been persuaded of this by a thoughtful essay by Steven D. Greydanus of the National Catholic Register, a mainstream writer who simply and concisely explains why. I mention this only to argue that a film can be blasphemous, or anything else that the director desires, and we should only hope that it be as good as the filmmaker can make it, and convincing in its interior purpose. Certainly useful things can be said about Jesus Christ by presenting him in a non-orthodox way. There is a long tradition of such revisionism, including the foolishness of The Da Vinci Code. The story by Kazantzakis, Scorsese and Schrader grapples with the central mystery of Jesus, that he was both God and man, and uses the freedom of fiction to explore the implications of such a paradox.

Now, I think that Ebert’s new essay offers a lot of insight into the film. For what it’s worth, I don’t think that it is right to say that it uses “the freedom of fiction to explore the central mystery of Jesus.” I think that Last Temptation uses the central mystery of Jesus as a metaphor, and that what the film is really exploring is the human experience of duality. Screenwriter Paul Shrader acknowledges this in an interesting 2002 interview at AVClub.com in which he acknowledges the film’s blasphemy:

Actually, the whole issue of blasphemy is interesting, because technically, the film is blasphemous, but not in the way people think. The film uses Jesus Christ as a metaphor for spirituality. And, under a technical definition of blasphemy, if Jesus is regarded as something other than holy God incarnate, you’re being blasphemous. And so the film takes the character of Jesus and uses Him as a metaphor for our spiritual feelings and says, “What if this happened, what if He yielded to temptation?”

I think Ebert makes essentially the same point when he says, “What makes ‘The Last Temptation of Christ’ one of his great films is not that it is true about Jesus but that it is true about Scorsese.” Be that as it may, where I differ from Ebert and other fans of the film is that, for me, my ability to enter the filmmaker’s world simply encounters an immovable obstacle when it comes to a Jesus movie that, however true it may be about the filmmaker, is so radically untrue about Jesus. I am just unable to go with Jesus as metaphor, for precisely the reason that Shrader indicates. I appreciate Ebert’s lament that “the direction, the writing, the acting, the images or Peter Gabriel’s harsh, mournful music” have been ignored by many writers — but for me that’s all beside the point. As I wrote in my essay:

Past a certain point, objectionability obliterates all hope or desire of approaching a work as art or entertainment. No level of production values or technically proficient filmmaking could make it worthwhile to watch a movie that indulged in child pornography, or that relentlessly celebrated the Holocaust, or that overtly romanticized the degradation and abasement of women. Cross a certain line, and message overwhelms medium, substance overwhelms style, what you have to say drowns out how you might be saying it.

Anyway, that’s how I saw it eight years ago. That this essay — one of my oldest pieces, an essay I wrote when I was first beginning to feel my way into the world of writing about film and faith — would receive such attention at this late date is both gratifying and humbling. I can’t even imagine how I would have felt back in 2000 writing the piece if you had told me that Ebert, whom I quoted in that piece, would one day be citing me in turn.

That the piece appears in Ebert’s Scorsese book is even more gratifying. As Nick Alexander suggested over at ArtsAndFaith.com, it seems likely that Scorsese has read Ebert’s book, so maybe he now knows that the movie is blasphemous, too.

Ebert’s new Last Temptation essay

Children of the Mind

There is no gap whatsoever between the stories of Xenocide and its successor, Children of the Mind. The latter picks up the story exactly where the former left off.

But between the books there was a five-year lag in the real world. Xenocide came out in 1991 and Children of the Mind in 1996.

Why would that be?–especially when, as Orson Scott Card explains in an afterword to the audio book version of Xenocide, that the two were originally one novel that got so long it had to be split in half.

My suspicion is that it was because Card simply had problems getting Children of the Mind to work. He talks periodically in his audio commentaries about how there were times he’d be writing something and it just wouldn’t be working, and he knew it, and it was only later that the solution occurred to him.

I suspect that, due to the time lag between the two works and the fact that there are minor inconsistencies between them, that Card just had a really hard time writing Children of the Mind because it wasn’t working.

Some would say that the novel still doesn’t work.

I’d be one of them.

And I’m not alone.

The very first thing he says in the audio commentary at the end of this fourth book is (I’m going by memory here), "A lot of people really hated a lot of things I did in this book."

He mentions in particular that his publisher hated a plot point that occurs at about mid-story in this book.

Personally, I didn’t hate that plot point, in which a character undergoes a transformation so dramatic that it’s debatable whether the character has technically died or not.

I felt profoundly ambivalent about it, mainly because by this point the character had become so tired of life that reading about the character was no longer interesting.

Still, I understand why people would be mad about it. What happens doesn’t provide the kind of resolution you expect at the end of a major character’s story arc. It feels like the character has just been whacked off into left field instead of being given a satisfying resolution.

Speaking of left field, that’s where it felt like a major plot point at the end of Xenocide came from, and that plot point dominates the present book. If you didn’t like the "Where did this come from?" twist at the end of Xenocide, you’re likely to have trouble with the new book, too.

On the religion front, the basic crypto-apologetic appeal for Mormonism that developed in the previous book remains in place.

The only real development is that now we have some dealings with a Japanese-colonized planet and a Polynesian planet, both of which are polytheistic.

On the Polynesian planet the Christian God is openly mocked as a (quotation from memory) "perfectly balanced Nicene paradox," while lesser, finite gods are jovially celebrated, with one of the powerful characters already established being acclaimed a living god by the Polynesians, with no cross-examination of this claim.

The thing that I really hate about this novel, though, is not the way it handles religion.

It’s the way it’s written.

Card has indulged his introspective tendencies so much that now he’s positively wallowing in them.

Vast swaths of the book feel like they were written according to the following formula:

- Something happens.

- Character A notices that something has happened.

- Character A tries to figure out how he feels about this.

- Character A reviews his entire life history and how the new event relates to it while trying to sort out his feelings.

- Character A decides that the thing is either poignantly beautiful, something to be serenely accepted, or something to be opposed as a cruel injustice of the cosmos.

- Character A wonders how Character B will regard the new event.

- Character A reviews the entirety of Character B’s life history trying to figure out what Character B will think and how logical or illogical that is.

- Character B notices the event.

- Characters A and B talk about the new event, leading to either a moment of supreme unity between them, a moment of resigned acceptance, or a verbally and/or physically violent confrontation, possibly followed by a tearful reconciliation.

- Go to Step 1.

Not all of these steps occur, or occur in the same order, every time something happens, but the plot just inches painfully forward amid reams and reams of introspective monologue or emotion-laden dialog.

By this point the series has become a brooding, science-fiction soap opera, with no plot development, however small, that can occur without being emotionally analyzed in excruciating detail.

The reader wants to scream, "CAN SOMETHING PLEASE HAPPEN HERE TO END ALL OF THIS INTROSPECTION!!!???"

Also in this novel the main character–Ender Wiggin–continues to become increasingly less relevant to moving the plot forward and ever more personally passive, though that doesn’t stop the other characters from obsessing at great length about Ender and what he feels and thinks about things.

While the plot proceeds with glacial slowness, the characters do eventually manage to deal with the planetkilling fleet that is now (finally, after three novels) poised to destroy Lusitania. How they do that is actually pretty cool, and has some nice humor elements in it.

But though we do get closure on that plot point, the novel leaves another, newer plot point completely unresolved–namely: "Who are the people who created the killer virus from the previous novels and why did they make it?"

It is this question that, in the audio afterword, Card said he felt too anticlimactic to answer in the novel or in a sequel, though he was besieged for years by fans wanting to know it.

Fortunately, he’s now decided that it is worth answering, and he plans a new novel that will connect the Bean fork of the series with the Ender fork that I’ve been reviewing.

Currently, I’m reading the Bean fork, and when I have it done, I’ll review it, too. (So far, I’m liking it much better than what happens in Xenocide and Children of the Mind.)

For my money, the first book of the Ender fork–Ender’s Game–is simply brilliant (and not in the phony, British sense of "brilliant"), and well worth reading. The second book–Speaker for the Dead–is brilliant but flawed. The third book–Xenocide–is probably debatably worth reading for the interesting stuff in it, but it is profoundly flawed. The fourth book–Children of the Mind–is simply the endlessly talky horse pill that you have to swallow if you want to get some kind of closure on the events set up in the previous three books.

NEXT (WHEN I’M ABLE TO RETURN TO REVIEWING THESE BOOKS): The first book of the Bean fork . . . Ender’s Shadow.

Xenocide

After Speaker for the Dead, we do not take another 3,000 year jump before the next sequel, only a 20-or-so year jump.

Why that long?

Because that’s how long it takes for the fleet of planetkilling starships to reach Lusitania at sub-light speeds.

Oh, yeah . . . Speaker for the Dead ended with a fleet of starships on their way to Lusitania with a planetkilling weapon.

That’s kind of a big, unresolved plot point.

Orson Scott Card has a tendency to leave major plot points unresolved at the end of his books. Sometimes it happens because his books get too long and he needs to cut them in half, but some of the time it is because the plot point deals with a question that just isn’t a priority for him.

As he explains in a commentary at the end of the audio book version of Children of the Mind, the last book of the Ender fork, where he leaves a similar big plot point unresolved, he just doesn’t feel that answering the question is that important. Either the answer is A or B, but the interesting part to him is the drama of the characters living with the tension of not knowing if it will be A or B. It would be kind of anticlimactic to reveal it, he essentially says.

I strongly disagree with this Sopranos-like school of storytelling. I think that if you’ve spent time setting up a major question in the story then you have implicitly promised the readers that you will give them an answer to this question. You may not owe them answers to every tiny issue that arises, but if you’ve staked major dramatic investment in something then you either owe them an answer in the current book or you owe them a sequel that answers it. Readers feel cheated if major elements of the story are left unresolved.

And eventually Card does get around to answering the question of whether the planetkilling fleet does or does not destroy Lusitania.

But not in this book.

That’s right. The planetkilling fleet that is out in space at the beginning of the novel is still out in space at the end of the novel.

In this case the thread is left hanging because the book got too long for Card and he had to cut it in half, but it still lessens the reading satisfaction that you get when the major threat driving the overall plot is still unresolved at the end of the book.

I thus think that Xenocide is a step down from Speaker for the Dead, which was itself a step down from Ender’s Game.

I don’t just feel this because the main driver of the plot is unresolved at the end. There are also other reasons.

For one, the story starts to get really talky. Card is an introspective writer (meaning: he spends a lot of time exploring characters feelings and motivations), and when he lets this tendency go too far it starts causing the plot to drag.

That starts happening in this book.

Basically, the characters are focused on three things: (1) Now that the Uber Prime Directive has been overthrown, can Humans and Piggies live together successfully, (2) How can we create faster-than-light travel to start evacuating the planet in case we can’t stop the planetkilling fleet, and (3) How can we stop a horrible virus that is too dangerous to be taken off Lusitania and that could devastate the biospheres of any planets that it is taken to as part of the evacuation?

Also, we get to meet characters on a Chinese-colonized world named Path and learn about their culture.

The first of the things that the characters are focused on is the most interesting dramatically (more on that in a moment). The questions of how to do FTL and how to stop the virus are kinda interesting, but the solutions to these questions more or less come out of the blue.

The characters in the story have Eureka moments after going down false paths, but they come across somewhat like when in a Star Trek episode the characters are trying this and that and then somebody hauls off and says, "Oh! I get it! We just need to reverse the polarity!"

There is also a HUGE plot twist right at the end of the book that just comes out of left field.

There are two kinds of plot twists: One in which, when it happens, you go, "Oh, yeah! That makes total sense! All of a sudden the earlier pieces now fit together!" The ending of The Sixth Sense is like that. It’s a twist that, while surprising, feels natural.

Then there is the "Where did that come from?" kind of plot twist–one that, while it may relate to things set up earlier in the story, does not seem to flow naturally from them but feels forced or arbitrary.

That’s the kind of plot point we get right before the end of the book.

I won’t spoil it; I’ll just note it as something that, again, diminishes the literary value of the book by asking the reader to make a big suspension of disbelief right at the climax.

So how does religion get handled in this book?

Well, we get a good bit about the religion of Path, which seems to be a development of Taoism. While he doesn’t go a lot into the doctrine of this religion–it’s a basic "honor the gods and ancestors" religion–it’s actually quite interesting because there is a certain class of people on path, known as the "godspoken," who are treated as holy people because they receive messages from the gods.

As soon as Card started describing how the godspoken receive their messages, a chill went up my spine because it was instantly clear that those to whom the gods "speak" are in fact sufferers of obsessive-compulsive disorder.

The "gods" give them feelings of profound unworthiness or uncleanliness (obsessions) and to relieve the anxiety these generate, they must perform ritualistic behaviors (compulsions), such as washing their hands over and over or tapping out rhythmic patterns with their foot or getting down on their hands and knees and visually tracing lines in the wood that the floor is made of.

I don’t know how I’d feel about this if I were a Taoist, but I find the idea of OCD sufferers being treated as holy people to whom the gods communicate is intriguing. That’s not what OCD is, but one can see how a real-world Human culture might have treated it as such. Later events in the story also make it clear that Card does not intend the role of OCD sufferers to be a slap at traditional Chinese religion.

He treats the religion of Path with respect, and one of the characters in the story ends up, after death, actually being worshipped as a god by the people of Path.

Back on Lusitania, the presentation of Catholicism continues to be problematic. Two devout characters get really good moments, and the community as a whole gets one really bad moment.

We have, in essence, a martyrdom, a pogrom, and the aftermath of the pogrom.

When one character is martyred for the faith, it is a very moving moment, and Card is really trying to do it right, even noting that the multi-hour debate that this character engaged in while being martyred was worthy of the disputations of the early Church Fathers.

The pogrom is much less successful dramatically. Oh, sure, it’s tragic when it happens, and you feel for the people who are getting hurt by it, but it just feels too much like cliches about torch-bearing Medieval fanatics willing to exterminate at the drop of a hat in the name of Christ, with people in the story actually brandishing torches, setting fire to things, and shouting that they’re doing this "For Christ!"

In the wake of the pogrom, the bishop of Lusitania gets his finest and basically his only fully-sympathetic moment as the previously stuffy and petty ecclesiastic reads the riot act to those who perpetrated the pogrom. He shames them profoundly and then announces a very moving public form of penance that the whole community will participate in, himself included, to atone for the events of the pogrom.

While Card is still trying to give the Catholic faith a fair shake, and while it’s nice to see the prickly old bishop finally (even though it is his last major scene in the novels) have a good moment, I still don’t think Card is fully successful.

Part of the reason is that it is in this novel that he starts working Mormon metaphysics into the story.

Up to now, he hasn’t done anything with the story that would imply the truth or falsity of any particular religion. He doesn’t tell us one way or the other whether the gods of Path are real or whether the Catholic God is real. Those are open questions that the characters in the story debate, but there are no definitive answers given by the author.

I’m comfortable with that.

But then he starts bringing Mormon metaphysics into things and it undercuts the religious neutrality he’s had heretofore.

Here’s how that works: Mormons believe in an endless series of finite gods who rule different worlds, often conceived of today as different universes. These beings reproduce, so there are new gods coming into existence through a process of development from unformed, uncreated eternal intelligences. One step in the process–for us at least–is being a human on the way to godhood. Mormons also believe that matter and spirit are essentially the same thing; spirit is just a more refined or subtle form of matter.

So here’s how that gets presented in the book: It turns out that all matter is made of tiny particles called philotes, which are bound together in various ways. These philotes have existed for all eternity, never having been created, in another realm called the "Outside," where they exist in a formless state, yearning (they’re at least all primitively conscious, so mind and matter are the same thing) to enter into relationships and exist in our world as part of physical objects.

Philotes come in different strengths, and inside each physical object is a master philote which is capable of holding all the others together so that the object doesn’t disintegrate. The strength of a philote needed to hold together a stone or a flower is less than the strength of the philote needed to hold together a human being. This master philote is called an aiua (eye-you-ah), but it could also be called a soul. Thus the souls of all humans have existed from all eternity in an unformed state and have grown and progressed by becoming incarnate with a bunch of other hylozoic pieces of matter.

And they can progress farther. We learn of one character who, it turns out, has a soul so powerful that he can not only animate one human body (his own) but simultaneously animate two other living human bodies as well. And one character (not the one from Path who ends up worshipped as a god) is even more powerful, having an aiua so strong that it is openly speculated that this character could be regarded as a god.

Perhaps this character could even one day bud off a new universe, because–it is speculated–there have been an infinite number of universes budded off by aiuas that got sufficiently strong in the previous universes, so there is an endless chain of universes stretching back in time with no beginning, just as there is no beginning to the philotes.

Sound familiar?

I don’t have a problem with Orson Scott Card exploring these ideas or writing a book that presents Mormon metaphysics in an imaginative form. Writers from any religious perspective can be expected to do that.

But what I don’t like is the fact that this starts forming an implicit anti-Catholic apologetic on the part of the novels, and that diminishes them artistically.

Mark Twain is alleged to have said that literature should never preach overtly but should constantly preach covertly. Card seems to be trying to follow that dictum, but he’s preaching so loudly that the art of the books suffers.

First, we have a largely unsympathetic Catholic culture, where all of the sympathetic Catholics hold their faith in a nuanced, attenuated way or are doubters or flat-out unreligious. Then we put this Catholic culture alongside a polytheistic one, with equal openness to the idea of multiple gods and the Christian God being real (compatible with the Mormon view). Then we get Mormon metaphysics thrown in and these metaphysics turn out to be true, because they provide the solution to the questions of faster-than-light travel and curing the killer virus that must be stopped.

So a Mormon writes a book that assumes Mormonism is true and Catholicism is false. What’s wrong with that?

Nothing.

But the art suffers. Card may be trying to give Catholics a fair shake–at least to a significant extent. though the fact that the series is now turning into a crypto-apologetic for Mormonism is starting to call that into question–but the art still suffers.

Here’s why: Suppose you’re a faithful Catholic on a planet in the year 5200 (approximately) and you start discovering that Mormon metaphysics is true, that we’ve all existed as unformed intelligences for all eternity, and that there is likely an eternity of universes, each created by a finite being, with no beginning and no first Creator to the whole series.

Do you:

a) Accept all this without question as the story rolls along, not noticing any problem? or

b) Sit down and have a major crisis of faith as you realize that the core of your religious beliefs appear to be false?

The second is what would happen in the real world. The first is what happens in Card’s book.

And that’s implausible, so the art suffers.

Card can’t let his characters have a crisis of faith without making it explicit that he’s having Mormonism trump Christianity, and that would violate Twain’s dictum about not overtly preaching because it diminishes the art. And it would diminish the art if the characters suddenly realized "Oh, wow, we’ve all got to become Mormons."

He can’t go there, so instead he leaves a planet-sized implausibility in how the characters deal–or rather fail to deal–with the implications that their discoveries have for their core beliefs about the world.

He may not be explicitly endorsing Mormonism in the book, but he’s implying it so strongly that the reactions of the characters become really implausible, harming the art.

Just as the book ends.

By the way . . . notice how I’ve managed to get almost to the end of a review of an Ender book without mentioning Ender?

That’s because, though Ender is in this book, he has progressively less and less to do.

The burden of moving the plot forward shifts to the rest of the cast, which consists principally of a family that Ender has married into.

And what a family it is! Everybody is either a genius physicist or a genius biologist or a genius xenologer or a genius without portfolio. Coupled with Ender’s own genius, we’ve got a lot of geniuses running around.

I could understand that in the first novel, where Ender was put in a school meant specifically for potential military geniuses, but by this point in the series the plot has become dominated by geniuses all over the place (including three more on the world of Path).

I suppose that Card might say, "Well, it’s the really intelligent people who end up being the most influential in world affairs, and geniuses tend to marry other geniuses, who already have children who are geniuses."

Maybe.

But it just feels a little . . . odd . . . literarily when absolutely all of the major characters in book after book turn out to be geniuses.

NEXT: Children of the Mind.

Speaker for the Dead

You might think that the sequel to Ender’s Game would be set shortly after the events of that novel.

Nope.

Instead, Speaker for the Dead is set 3,000 years later, yet it still continues the story of Ender Wiggin.

How does that work? Is he an immortal being? Has medical technology banished death? Or perhaps time travel is involved. Or cryonic suspension.

Actually, it’s as mundane as the known effects of relativistic spaceflight. After the events of Ender’s Game, Andrew "Ender" Wiggin left Earth for the stars, and the only way to get there in his universe, as in ours, was by slower-than-light travel.

So while 3,000 years have passed for mankind by the time the novel begins, far fewer have passed for Ender, and he’s now a young-ish adult.

In those 3,000 years mankind has moved out into the stars and set up colonies on different worlds.

The world that is at the core of this novel is called Lusitania–the ancient name of Portugal–and it is so named because it is inhabited by Portuguese-speaking colonists from Brazil.

It is also inhabited by the second intelligent race mankind has found in the universe.

The first was the Buggers, and things went very, very badly with them. Mankind is determined not to make the same mistakes that it made with them.

The new race, known in Portuguese as the Pequeninos or "Piggies" because of their snouts, are a small, unintimidating, technologically primitive, forest-dwelling race.

But as soon as it’s found out that they have intelligence and language, mankind’s government slaps draconian restrictions on the Lusitania colony that are like the Prime Directive on steroids.

A fence must be build around the colony, whose population must now be sharply limited. The colonists must have virtually no contact with the Piggies except for two xeno-anthropologists (xenologers or xenodors) who are allowed brief, daily contact with the Piggies with the condition that they do not show human technology to them or disclose information about human society or ask questions about Piggie society that would betray human expectations of what our society would be like.

It’s maddening.

But there is a mystery on Lusitania, and the Piggies are closely connected with it.

When one of the xenologers figures out the secret, the otherwise friendly Piggies suddenly, brutally kill him.

Then they act like nothing is out of the ordinary, and the surviving xenologer can’t even ask why this was done, due to the Uber Prime Directive.

But Andrew Wiggin is called in from a nearby world to speak the death of the xenologer who was killed.

Since the events of Ender’s Game, Ender has become a speaker for the dead. This is a person who, after someone has died, performs a service (a "speaking") in which the person’s life story is reviewed and analyzed in such a way as to make sense of it. It’s not the same thing as a eulogy, because in a eulogy you say nice things about the dead. In a speaking you say honest things about them. That includes the nice, but it also includes the ugly. And yet the effort is made to understand the ugly things a person did and why he did them.

It takes twenty years for Ender to arrive on Lusitania due to slower-than-light travel, but he appears and must penetrate the mystery of the planet in order to perform his duties as speaker for the dead. He must find out why the xenologer was killed.

Speaker for the Dead is a very different novel than its predecessor. It is much more an adult novel, about ideas and adult relationships rather than kids and games and kid relationships. There are no sex scenes in the book, though there is substantial discussion of human reproduction and adultery.

It is also different in that we have a real alien environment in this novel, and much of the plot centers on figuring out the mystery of this environment and the Piggies who inhabit it.

It is a very good novel, and it also won both the Hugo and Nebula awards the year it came out (1986, the year after Ender’s Game, making Orson Scott Card the first author to win both awards two years running).

In a postscript to the audio book version, Card notes that readers are often divided about whether Ender’s Game or Speaker for the Dead is the better novel and that his idea of an ideal world is one in which people are evenly divided on this question.

Given how different the books are, it’s a bit of an apples and oranges comparison, but there is an answer to it, and I’ll tell you what it is . . .

Ender’s Game is better.

The reason is that, while both books contain very good elements, the sequel contains a prominent flaw due to the limitations of Orson Scott Card’s religious imagination.

Card is a Mormon, but the world he’s writing about has been colonized by Catholics.

That much is fine. It’s quite possible for a person of one faith to write convincingly and even movingly about the people of another. The guy who wrote A Man for All Seasons wasn’t Catholic, but he was able to tell the story of St. Thomas More beautifully.

But to do this kind of thing you have to be able to put yourself in the shoes of someone of a different faith in a way that Card can’t quite pull off.

It’s not that he doesn’t try. He thinks that he’s giving the Catholics a fair shake, showing good ones and bad ones, showing faithless and faithful ones, showing the joys and sorrows that apply to everyone regardless of their religion, even having a moment where Ender wants to weep because of the beauty of the poignancy involved in a married religious order (the Children of the Mind of Christ) where the spouses renounce sexual relations to better serve God, while still living together in a monastic environment.

But ultimately Card can’t do it.

In real life, Card spent time as a Mormon missionary in Brazil. He went there to convert Catholics, and he’s drawing upon his experiences there to shape his depiction of Lusitanian society.

The society he shows us is largely repulsive, with the vast majority of Lusitanians being insular, blindly obedient followers of the unsympathetic, rigid, uncompassionate bishop who opposes Ender at every turn and only starts to friendly up once Ender points out to him that, if they throw off the Uber Prime Directive, he will be able to evangelize the Piggies.

The problem is not that Card shows bad Catholics. The world has many bad Catholics, just as it has many good ones.

The problem is that the only good Catholics that he shows us are those who take their faith least seriously. The sympathetic Catholic characters are the ones who struggle with their faith or question or doubt it or who even have virtually no faith at all. (Ender falls into that category; he was baptized Catholic but not raised in the faith.)

Those who take their faith seriously end up being presented as harsh, insular, intellectually simple, under the domination of their bishop, and suspicious of outsiders like Ender.

The message that comes across is: simple, devout Catholics = bad; sophisticated, doubting Catholics = good.

All this is like the reception that a Catholic culture in Brazil might give to a visiting Mormon missionary, like Card.

Thus this novel is not as good as its predecessor. It’s still very good, and still worth reading, but it is also flawed. Card chose to set his story on a Catholic world; he chose to make religion a prominent theme in the novel; but he either wasn’t able or wasn’t willing to do artistic justice to a Catholic culture.

NEXT: Xenocide.