I’ve had several requests to comment on the announcement in the Diocese of Phoenix that Sr. Margaret McBride of the Sisters of Mercy (pictured) has incurred automatic excommunication for approving an abortion at St. Joseph’s Hospital and Medical Center in Phoenix.

I’ve had several requests to comment on the announcement in the Diocese of Phoenix that Sr. Margaret McBride of the Sisters of Mercy (pictured) has incurred automatic excommunication for approving an abortion at St. Joseph’s Hospital and Medical Center in Phoenix.

So here goes.

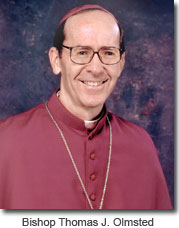

As you would expect, Bishop Olmsted of Phoenix is being pilloried in connection with this, with the mainstream media and others trying to fit it to the “Cruel Bishop vs. Victim Nun” stock narrative (as opposed, e.g., to the “Conscientious Bishop Trying To Do His Job after Nun Approves Horror” narrative).

So let’s try to take an objective look at the situation, starting with the facts of the case.

Unfortunately, the facts of the case are not entirely clear. The identity of the mother who had the abortion, for example, has not been disclosed due to medical privacy laws, but here is what we know:

1) Last December a 27-year old woman with pulmonary hypertension was 11 weeks pregnant and sought some form of care at St. Joseph’s Hospital and Medical Center in Phoenix.

2) According to a statement of St. Joseph’s, a consultation was held “with the patient, her family, her physicians, and in consultation with the Ethics Committee, of which Sr. Margaret McBride is a member.”

3) It was decided that “the treatment necessary to save the mother’s life required the termination of an 11-week pregnancy.”

4) The abortion was performed, though the means by which it was done is not clear. Presumably it was suction aspiration, or possibly dilation and curettage since RU 486 does not seem to be recommended for 11 pregnancies. The Arizona Republic states that it was a “surgery,” which would also point to either suction-aspiration or D & C, but it mentions this only in passing, and so it could be something the reporter assumed, not what actually happened. If it was (as I strongly suspect), suction-aspiration or D & C then the child was directly torn in pieces as part of the procedure.

5) At some point this came to the attention of the Diocese of Phoenix, and Sr. McBride confirmed to Bishop Olmsted that she had approved the abortion.

6) At some point, presumably after this, Sr. McBride was reassigned within St. Joe’s. Neither the diocese nor the hospital has said whether Bishop Olmsted had a role in the reassignment.

7) Also at some point, presumably at about the same time, Sr. McBride was informed that she had incurred a latae sententiae (automatic) excommunication per canon 1398 of the Code of Canon Law, which states: “A person who procures a completed abortion incurs a latae sententiae excommunication.”

8) At some point the reassignment of Sr. McBride came to the attention of the Arizona Republic, whose staff contacted both Bishop Olmsted and St. Joseph’s for statements.

9) On or about May 14, St. Joseph’s confirmed to the Arizona Republic that an abortion had taken place there in December. On or about this same date it provided a statement to the newspaper.

10) On May 14, Bishop Olmsted provided a statement as well.

11) On May 15, the Arizona Republic published the statements online (kudos to the Arizona Republic for doing so instead of hiding them and merely quoting and summarizing them without showing us the context).

12) The same day, it published this story by Michael Clancy on the matter (for some reason the story now carries a date of May 19, though it originally came out four days earlier; perhaps this is an unacknowledged revision of the original story). It was at this point the story became known to the public in general.

And those are the basic facts as we know them (or seem to know them).

Let’s see if we can answer a few questions:

1) Is the bishop really being mean?

From the way this is being reported, you’d think that Bishop Olmsted was issuing thundering public denunciations of Sr. McBride, that he took the initiative to sent out some kind of press release announcing the excommunication, perhaps to warn members of his flock that Sr. McBride is to be publicly shunned or something.

From what I can tell, this is the exact opposite of what happened. It appears that Bishop Olmsted issued his statement only in response to the hospital confirming the story for the press. Had the hospital kept its mouth shut, Bishop Olmsted would not have made it public.

To minimize public humiliation of Sr. McBride, Bishop Olmsted did not say in his statement that she had been excommunicated. In fact, she was not mentioned in his statement at all. The only mention of excommunication the statement makes is a general one, with no specific individuals in focus. It is just the general caution, “If a Catholic formally cooperates in the procurement of an abortion, they are automatically excommunicated by that action.”

Reporter Michael Clancy also seems to acknowledge that the Bishop did not speak explicitly of Sr. McBride, stating in his story only that he “indicated” (as opposed, e.g., to “said”) that McBride was excommunicated.

My guess is that what happened here is that the Bishop wanted to deal with these matters privately, but someone at the hospital tipped the press, which then asked both the Bishop and the hospital about the matter. When the hospital confirmed, the Bishop felt obliged to respond as well, but of a desire to protect the reputations/privacy of those involved, he responded only in general terms, acknowledging that an abortion had taken place, that he was horrified by this, and explaining the Church’s position on such matters.

Scarcely the “Cruel Bishop vs. Victim Nun” narrative. No thundering public denunciations of Sr. McBride; no attempts to publicly shame her—quite the opposite!

But the press ran with it, making explicit the fact that she had been excommunicated. The bishop hadn’t said so, but presumably she and/or someone else who knew about it told the Arizona Republic, and the Arizona Republic took the reference to the Church’s law in the bishop’s statement as confirmation.

The story then went all over the place, and the diocese felt obliged to provide a Q & A to clear things up.

This Q & A was released on May 18th by Rob DeFrancesco, the diocesan director of communications. It is online here (.pdf), and it seems to have been written by the communications office, because it contains a number of imprecisions regarding canon law that Bishop Olmsted, who is himself a canonist, would not be expected to use in his writing.

The document is notable, though, in that it confirms that Sr. McBride—and ostensibly others (none of who are named)—automatically excommunicated themselves due to their involvement in the abortion.

Again, this does not support the narrative of a bishop being cruel by publicly humiliating someone. Instead, it suggests a bishop trying to preserve the reputations and privacy of all involved but feeling compelled by the press to reluctantly confirm certain facts in order to prevent public misunderstanding.

2) Did Sr. McBride automatically excommunicated herself?

This is an important question, because if she did then one can scarcely fault Bishop Olmsted for informing her of this fact. It would be his duty as a pastor to inform her of the canonical consequences of her action and encourage her repentance and reconciliation with the Church. In other words, he would be doing his job, seeking to encourage reconciliation in the wake of a tragic error.

So . . . did she?

As outsiders, it’s hard for us to say for ourselves because the specific facts of the case aren’t known. Bishop Olmsted has sought to preserve Sr. McBride’s privacy, and according to Catholic News Service, “Sister Margaret . . . has declined to comment on the controversy.”

But let’s look for a moment at the law as it seems to apply to this case.

According to canon 1398, quoted above, a person who “procures a completed abortion” incurs automatic excommunication. Among other things, this must be understood in light of subsequent Magisterial teaching (e.g., Pope John Paul II’s encyclical Evangelium Vitae) as referring to a “direct abortion, i.e., every act tending directly to destroy human life in the womb ‘whether such destruction is intended as an end or only as a means to an end’” (EV 62).

This excludes procedures that do not directly kill the child but that foresee the child’s death as a non-intended, non-desired side effect (e.g., radiation or chemotherapy treatments for a pregnant mother with cancer). It is also why I dealt above with the fact that the child was almost certainly killed by suction-aspiration or dilation and curettage, both of which tear the child into tiny bits and are thus unambiguously the direct killing of an innocent individual, with no dispute possible, even hypothetically.

So far as we can tell, there is no dispute that a direct abortion occurred in this case, meaning that this part of the question is off the table.

So did Sr. McBride “procure” such an abortion?

Before we answer this question, we must mention another canon that has relevance to this case. Canon 1329 provides that:

§2. Accomplices who are not named in a law or precept incur a latae sententiae [automatic] penalty attached to a delict [offence] if without their assistance the delict would not have been committed, and the penalty is of such a nature that it can affect them . . .

One might hold that only the woman who has an abortion and/or the one who pays for or arranges for it “procures” it, but canon 1329 makes it clear that the penalty of automatic excommunication also applies to accomplices “if without their assistance the delict would not have been committed.”

So one can either argue that by voting to approve the abortion Sr. McBride fell under the provision of “procuring” the abortion or that she functioned as a necessary accomplice under the provision of canon 1329 §2.

In either case, she would have incurred automatic excommunication.

Thus Bishop Olmsted would have been simply doing his pastoral duty of informing her of the fact that she had excommunicated herself and needed to take steps to reconcile with the Church.

3) Is there another option?

Suppose that Sr. McBride did not “procure” an abortion and that she was not a necessary accomplice in procuration one. Is there a theory that would allow her to be seen as automatically excommunicating herself?

Maybe.

Such a theory seems to be suggested by the Q & A that the Communications Office of the Diocese of Phoenix released.

This Q & A states:

Why was Sr. McBride excommunicated?

Sr. McBride held a position of authority at the hospital and was frequently consulted on ethical matters. She gave her consent that the abortion was a morally good and allowable act according to Church teaching. Furthermore, she admitted this directly to Bishop Olmsted. Since she gave her consent and encouraged an abortion she automatically excommunicated herself from the Church. “Formal cooperation in an abortion constitutes a grave offense. The Church attaches the canonical penalty of excommunication to this crime against human life.” (Catechism of the Catholic Church #2272) This canonical penalty is imposed by virtue of Canon 1398: “A person who procures a completed abortion incurs a latae sententiae excommunication.

The significant part of this is the quotation from CCC 2272, which states that formal cooperation in an abortion is a grave offense to which the Church attaches the penalty of excommunication.

Formal cooperation is a much lesser test than that provided for in Canon 1329. To formally cooperate with an act one need only cooperate with it (as Sr. McBride clearly did by voting to approve the abortion) and approve of it (as she did if she consented to it as “a morally good and allowable act,” per the Q & A). This involves much less than being an accomplice without whom the offense “would not have been committed.”

Still, an unquoted part of the Catechism text notes that this application is “subject to the conditions provided by Canon Law” (presumably including Canon 1329). It then references Canons 1323 and 1324, neither of which seem apropos to this case.

Nevertheless, it seems that the Communications Office of the Diocese of Phoenix may be holding to a theory that, based on CCC 2272, any formal cooperation with a direct abortion will trigger automatic excommunication, and if it is true that Sr. McBride “gave her consent that the [direct] abortion was a morally good and allowable act according to Church” then it seems she formally cooperated in such an abortion and triggered the penalty on this theory.

There would be several defenses against this view (among them: The Catechism is a teaching document that does not establish legal requirements; also, Canon 18 requires that a strict interpretation be given to laws involving the penalty of excommunication).

And the theory just articulated is not the common understanding among canonists, which is one reason why the Q & A seems to contain imprecisions that one would not expect of Bishop Olmsted as a canonist, but it deserves to be mentioned since it’s in the Q & A.

MORE FROM CANONIST EDWARD PETERS.

What are your thoughts?

Remember how President Obama promised that his health care legislation wouldn’t cover abortion?

Remember how President Obama promised that his health care legislation wouldn’t cover abortion? The odds that it is being infringed went down this week when, among other things, the U.S. Supreme Court issued

The odds that it is being infringed went down this week when, among other things, the U.S. Supreme Court issued  So Helen Thomas has

So Helen Thomas has  I thought I would take the opportunity to offer a few thoughts on some of the issues raised in the combox of my

I thought I would take the opportunity to offer a few thoughts on some of the issues raised in the combox of my

From Canada’s National Post comes

From Canada’s National Post comes