This version of The Weekly Francis covers material released in the last week from 22 August 2016 to 10 June 2020.

This version of The Weekly Francis covers material released in the last week from 22 August 2016 to 10 June 2020.

Angelus

Daily Homilies (fervorinos)

- 10 May 2020 – Praying is going with Jesus to the Father who will give us everything

- 11 May 2020 – The Spirit teaches us everything, introduces us to mystery, makes us remember and discern

- 12 May 2020 – How does the world give peace, and how does the Lord give it?

General Audiences

Letters

Messages

Papal Tweets

- “It is important to bring together scientific capabilities – in a transparent and disinterested way – in order to guarantee universal access to essential technologies that will enable every person, in every part of the world, to receive healthcare.” @Pontifex 4 June 2020

- “Everything is interconnected: Genuine care for our own lives and our relationships with nature is inseparable from fraternity, justice, and faithfulness to others. #LaudatoSi #WorldEnvironmentDay” @Pontifex 5 June 2020

- “The Heart of Christ is so great it wants to welcome us all into the revolution of tenderness.” @Pontifex 5 June 2020

- “The Spirit loves us and knows everyone’s place: for Him, we are not bits of confetti blown about by the wind, but irreplaceable fragments in His mosaic.” @Pontifex 6 June 2020

- “The feast of the #MostHolyTrinity invites us to let ourselves be fascinated by God’s beauty, goodness and inexhaustible truth. He is humble, near, who became flesh in order to enter into our history, so that every man and woman may encounter Him and have eternal life.” @Pontifex 7 June 2020

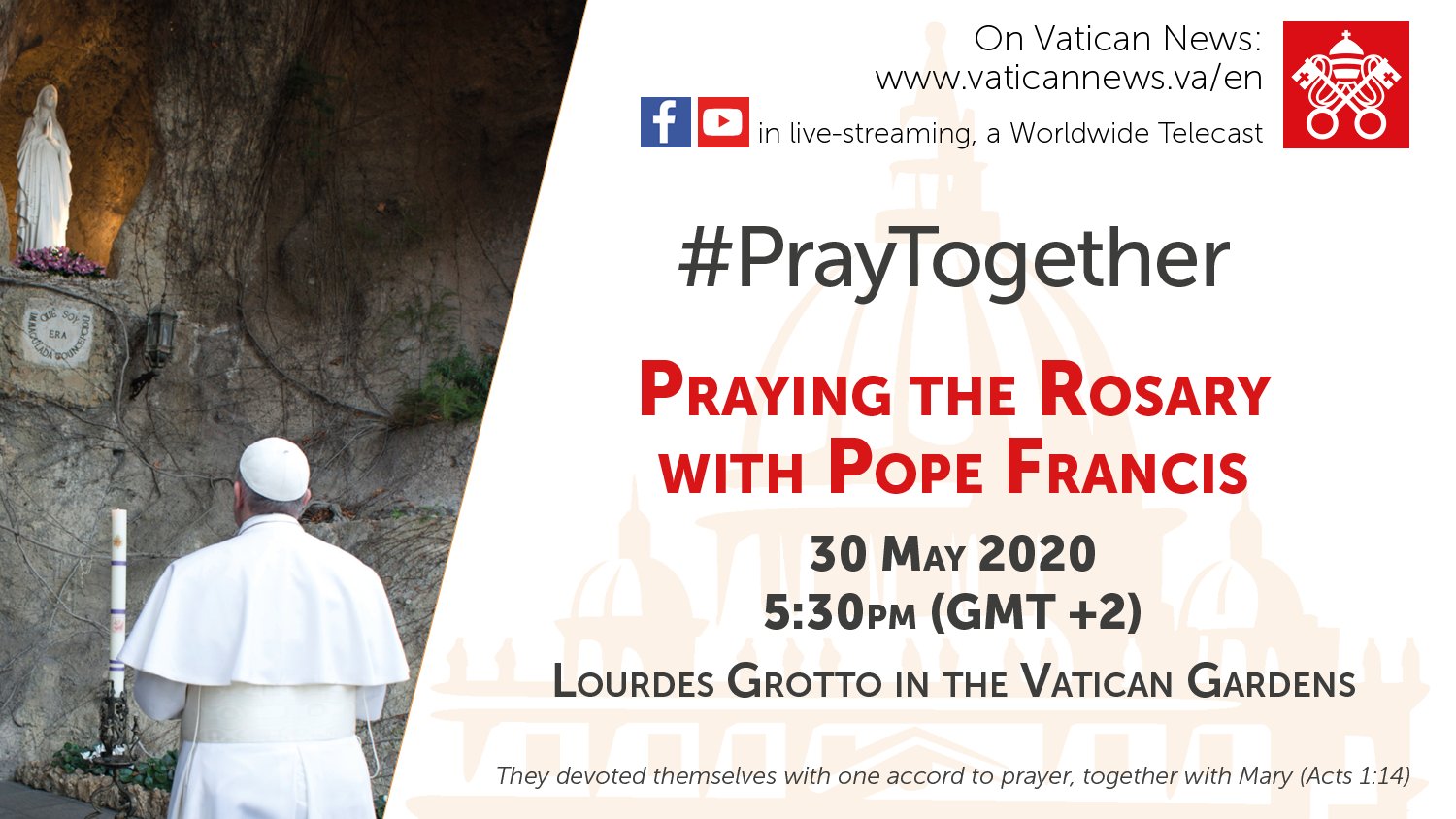

- “In many nations #Covid19 continues to claim many victims. I wish to express my closeness to those populations, to the sick and their families, and to all those who care for them. #PrayTogether” @Pontifex 7 June 2020

- “The #Beatitudes teach us that God, in order to give Himself to us, often chooses unthinkable paths, perhaps the path of our limitations, of our tears, of our defeats.” @Pontifex 8 June 2020

- “There are two Christian responses to escape the spiral of violence: prayer and the gift of self.” @Pontifex 9 June 2020

- “In our darkest moments, when we sin or are disoriented, we always have an appointment with God. We do not need to be afraid, because God will change our hearts and give us the blessing reserved for those who allow Him to change them. #GeneralAudience” @Pontifex 10 June 2020

Papal Instagram

”

”